September 10 – October 31, 2015

Opening reception: Thursday, September 10th from 5-7pm

Bevan Ramsay: Lesser Gods

Beyond Sociology: The Act of Seeing a Person

Text by Edwin Janzen

It is hardly surprising that in our society perceptions of homeless persons remain two-dimensional, stereotypical, inadequate. Even for the rare administration tackling the problems of homelessness in an effective, meaningful way, the homeless person’s humanity is buried beneath a mountain of endless statistical markers: mental illness, substance abuse, soup-kitchen attendance, etc. The enormous negativity lingering about the resultant profile permits scant room for other, arguably important accoutrements of the human experience—character, emotion, intellect, beauty, relationship to divinity—and leaves homeless persons basically where they already are: on the street, the objects of middle-class loathing or pity.

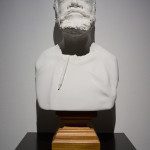

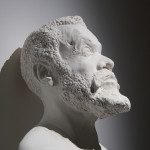

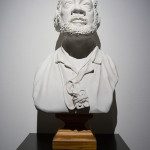

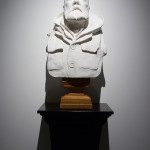

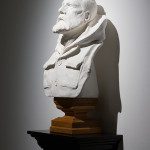

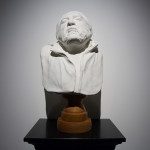

Struck by this depressing determinism, artist Bevan Ramsay set out to cast portrait busts of homeless persons (one woman, the others men), producing an edition in fine, white statuary Hydrocal plaster mounted on mahogany bases. These portraits, titled Lesser Gods, are objects of fine craftsmanship, skillfully rendered and strikingly beautiful, and they permit us to reconsider these folks not through the screen of stereotypes or statistics, but as individuals, complicating our urge to pity.

A Montrealer by upbringing, until recently Ramsay lived and worked out of New York, a city in which homelessness is closely contiguous with the city’s history and identity. In a certain irony, homeless people are statistically more likely to be native to New York than most New Yorkers. Yet, although they are more closely tied to place than the housed citizens (including Ramsay) of this intensely transplanted city, they are politically non-existent.

Accordingly, Ramsay spent many hours in conversation with his portrait subjects, getting to know them and letting them determine the course of the discussion. Most were open and forthcoming; only one remained demure. Biographical details were left out for privacy’s sake. Mindful of the need to respect person and character, and confronted by complex, daunting ethical issues, Ramsay did not rush to realize the project.

Baroque portraiture supplied Ramsay with an art-historical antecedent; with its emphasis on asymmetry, such portraiture yields greater charismatic possibilities than classical traditions. Rather than ideals or types, baroque portraiture insists on character, allowing the artist’s subjects to be “immortalized in high style,” as Ramsay explains.

We experience ourselves suddenly free to appreciate each subject’s facial expression and attitude, decisions on hair and beard grooming, or jacket style. And in Ramsay’s plaster, quite similar to porcelain, there is neither stench nor besmirchment—no abjection, no “street”—and we begin to understand what it is about homelessness that so terrifies the middle classes in the age of austerity. This guy—he could be you or me. Your son or my father. Our brother.