November 4 – December 20, 2017

Opening reception: Thursday, November 9, 2017 from 5-8 p.m.

Nicholas Crombach: Behind Elegantly Carved Wooden Doors

Art Mûr, Montreal (QC)

Text by Martha Robinson

At the beginning of Diana Donald’s essay on the hunting myth in Picturing Animals in Britain the author describes a “division of feeling intrinsic to the sporting mentality” in line with “contradictions at the heart of all human dealings with the animal kingdom.”1 Donald will locate these contradictions in Victorian-era visual culture, but she is careful to note these contradictions are still at play in contemporary British society. Nicholas Crombach has mined art historical tradition for Behind Elegantly Carved Wooden Doors, assembling a body of work rich in citation which nevertheless speaks directly to these contradictions. The visual language of sport hunting over the course of history informs much of the work; incongruities exist within those existing art historical traditions, and too, manifest in the reconfiguring of forms and traditions that plays a role in Crombach’s practice.

Inanimate Beings (2016) embodies these incongruities, clearly citing seventeenth-century game painting, including the occasional inquiring hound and the anthropomorphically, elegantly draped animal bodies found in Frans Snyders’ gamepieces. At the same time, the work is materially linked to Crombach’s Ornaments I, II and III, the reconfigured duck decoys which grace the walls in this exhibition, and the antiquity-inspired Memento (2017). Nathaniel Wolloch has highlighted contradictions intrinsic in game painting as a genre, and Snyders’ works in particular: an anti-Cartesian sentiment demonstrated by the careful rendering of the animal body, signalling a “pre-recognition of animal suffering” and “an obvious attempt to conceal or beautify the violent aspect connected with the killing of animals.”2 In citing the visual tropes of game painting, Crombach neatly layers such concerns with his own, his intention to “explore notions of innocence, shame and the dilemma of how to deal with and assess the relevance, and importance” of field sports and hunting traditions in the twenty-first century.

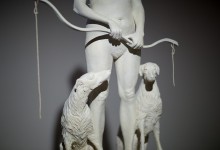

Contradictions realized in Crombach’s work are sometimes accomplished through the unexpected gesture or detail: the aged Diana and Actaeon (2016), Diana’s bow string broken; the collapsed rocking horse as End of the Chase (2015). With End of the Chase and Fair Game (2017), both of which adopt the aesthetic of nineteenth century children’s book illustrations—think Randolph Caldecott—tension is produced by the juxtaposition of an innocence inherent in their visual forms with ideas of the hunt, the collapse of the hunt-as-institution, and furthered by the disruption in function that the pull toy, rocking horse and decoys share.

As with Inanimate Beings, multiply references are embodied in these works: the rocking horse representative of horses lost in Victorian-era hunts; Crombach’s Actaeon, long past the age he was torn asunder as the stag-Actaeon, disrupting our understanding of that mythical hunt. The disruptions in form, function or history in Behind Elegantly Carved Wooden Doors consider, as the artist states, “a history of hunting; its cultural significance and the dilemmas present within, including current day,” and a history of vanishing craft traditions, employing the rich visual culture of the hunt to assemble a bricolage of works which revel in contradiction.

1. Diana Donald, Picturing Animals in Britain: 1750–1850 (New Haven CT: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2008),273.

2. Nathaniel Wolloch, “Dead Animals and the Beast-Machine: seventeenth-century Netherlandish paintings of dead animals, as anti-Cartesian statements,” Art History 22.5 (1999): 719.