Tromper l’oeil : Mathieu Cardin, Hédy Gobaa, Holly King, Guillaume Lachapelle, Marie-Claude Lacroix, Erik Nieminen, Greg Payce, Karine Payette, François Quévillon, Matt Schust, Gilles Tarabiscuité

Texte de Béatrice Larochelle

Deceit, lies, trickery – these actions are often frowned upon. On the other hand, illusion is an exercise from which it’s possible to come out as a winner, or not, either perceptive or credulous.

Isn’t it the first reaction of a spectator to look for the catch when the magician’s assistant is sawed in two? It seems that humans do not like to be caught up in the game, especially when they are not given the rules. The history of art, however, is entirely made up of simulacra. What could be more fake than an oil landscape on a canvas?

Despite all this, fascination takes hold of us when we realize our eyes are playing tricks on us. The artifice remains, after all, a fertile ground to our imagination and our enchantment. It pushes our interest and curiosity towards unexplored horizons. Tromper l’oeil is presented here as a point of drift, a reversal of notions of reality and fiction, a loss of anchorage in a wavering world. The participating artists are causing a shift towards an intriguing universe where fiction meets magic.

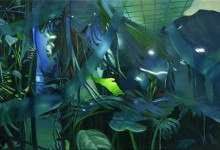

Like Marie-Claude Lacroix and Matt Schust, some use painting to blur our reference points. They shape worlds where codes are blurred, where materials blend together. Erik Neiminen and Hédy Gobaa, with the same medium, conceive distorted spaces that lose their meaning in the viewer’s eye.

Others use more complex subterfuges to deceive our vision. François Quévillon chose the medium of video and lenticular printing to simulate the mutation and displacement of organic objects. Karine Payette, known for her truer than nature installations, playfully proposes fictitious situations and phantasmagorical objects, immersing the viewer into a strange discomfort. As for Gilles Tarabiscuité, the artist reverses the notion of deception to create “pure” truths. Thwarting the first impression of digital modification, he suggests photographic images without any alteration, so-called absolute photographs.

But what about these artists who reveal their stratagem to us, inviting us into their secret world? Through her viewing boxes, Holly King reveals to us how she cobbles together her spellbinding landscape photographs. As if we were stepping into a fairy tale, we can find in her work the play of sizes, perspectives and deceptive materials that allow the creation of a narrative inspired by the great painters of sublime and romanticism. Mathieu Cardin, for his part, exposes a window on the backstage of his decoy. Playing with the tension between mirage and tangible, Cardin deceives the viewer, then shows how his artifice works. It is difficult to say whether the aesthetically composed confession is itself trying to deceive us. It’s in this perspective that Tromper l’œil gathers two distinct devices, make believe and revelation.