Melvin Charney: La ville en mouvement

Introduction by Gwendolyn Owens

Melvin Charney came of age at the moment when North American cities were being blown apart, not by enemy bombs, but by their own leaders and politicians in the urban renewal of the 1960s. Tall buildings were replaced by taller ones. Blocks of housing became blocks of voids as buildings were destroyed and replaced by nothing as shifting priorities and preoccupations distracted city officials. Sameness begot more sameness in boring, uncreative architectural projects.

Although Charney studied architecture, he designed no skyscrapers or houses. Instead, he was destined to use his knowledge of architecture to make art to make us see buildings and the city differently. In artworks ranging from temporary installations to permanent site-specific sculptures—some that were built, some only proposals—and extraordinary two-dimensional works of art, he took on the challenge of critiquing the new urban order. He used what he learned travelling—photographing what he saw—and reading broadly across many subjects, to add depth to his work: not just depth of form but depth of meaning in references to artists and places, both near and far away. He saw beauty in temples in Turkey and beauty in working class housing in Trois-Rivières.

In Charney’s works, buildings are living, breathing entities. The narrow legs in the running buildings look feminine. Do buildings, which like people, have bases or feet, bodies, and heads or tops, have a sex? Are these running female buildings? Various architectural blobs on the grid are over laid on advertisements for She-Males from the back pages of magazines. The all-purpose sex objects and the all-purpose blob building put together all on the same page.

Scientists say we learn best when we are interested and amused. Melvin Charney had some serious messages, but knew that the best way to interest his audience was by fascinating them with art that was exciting, intriguing, often colorful and sometimes a little racy. He died in 2012, and while there will be no more new Charney works of art, we will still be charmed for a long, long time by what he left for us to ponder.

Facing the Golem

Text by Edwin Janzen

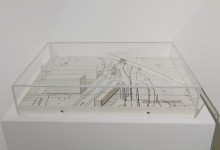

The artistic work of Melvin Charney (1935–2012) invites us to break through the wall traditionally separating art from “functionalist” architecture. Also a professional architect—and a lifelong student of the built worlds of Montreal—Charney understood that the symbolism of art also functioned within architectural forms. As an artist, he set architecture free from functionalism to speak on its own terms, in its own voice.

Charney’s representations of buildings, unpeopled and thus functionless, exert themselves. Some are ambulatory. Others toy with anthropomorphism, even as their gaping doors and windows fail to produce satisfyingly symmetrical happy-faces. Here we see the structures of industrialism uncoupled from its Smithian conceits (productive labour, increase of trade, etc.). Indeed, Charney’s works place us in a vantage point that seems to predate industrialism, a situation somehow medieval, unaffected by Enlightenment liberalism, and deeply, sternly critical.

Positing a perceptual time machine, what might factories and tenements mean to people of the Middle Ages? Charney himself sought such medieval comparisons, invoking the Jewish tradition of the golem (Hebrew: “unshaped form”) in certain works. A creature fabricated of mud, a golem was brought to life by inserting into its mouth a shem, a small paper inscribed with one of the names of God. Created to do a wise rabbi’s bidding, golems are better known from late medieval tales in which they slip their bonds and go berserk. The golem’s chief deficiency is its inability to speak—yet for anyone who faces one, probably its rampage would be sufficiently expressive.

Charney recognized that buildings, even abandoned ones, are like golems—expressive, inquiet—and he used their symbolic language in his art. In permitting us to hear this language, Charney uncovers haunted landscapes within industrial capitalism, a kind of spiritual or emotional underworld somehow impervious to penetration by liberal notions of progress.

One can understand how Marx, ruthlessly critical of capitalism yet impressed by its dynamism, might have embraced the notion that capitalism will create the tools for its own destruction. It’s a bleak emotional place, facing the golem—and how little has changed! Today’s berserk golems are built of brick and brushed steel, with cheap, smoked-glass balconies, but their forward march seems as inexorable. Reach into the mouth, if you will, and pull out the shem, but the golem just keeps on coming. Those who resist are swept away to marginal locations (Ville Émard, Laval) or content themselves with band-aid measures. That the monster will somehow destroy itself is an attractive fantasy.