David Umemoto: Vernaculaire Extraordinaire

Text by Nancy Webb

Over the past two years, we have perhaps contemplated every curve, every corner and every speck of dust in our apartments and homes more than ever before—out of boredom, out of entrapment, out of curiosity. We may have begun to notice dismal patterns, or dream of new spaces, grander and more interesting interiors that hold alternate lives with more optimistic outlooks. Many of us have thrown ourselves into DIY home projects, small renovations or spent endless, elysian hours browsing Realtor.ca, fantasizing about guest bedrooms and bay windows for reading in. We dream of other cities with novel sensory information, and remember the way that sirens and voices echo differently in faraway places.

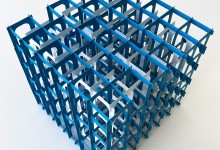

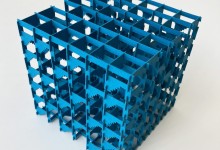

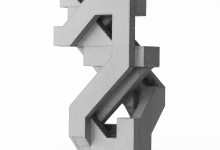

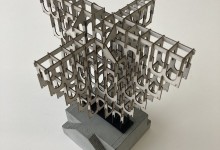

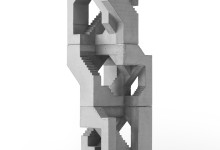

David Umemoto’s Vernaculaires Extraordinaires—a suite of iterative structures in concrete, plexiglass and paper—recalls this contradictory state we’ve been in, characterized by months of intense scrutiny pitted against hopeful daydreaming. His repeating arches and columns with occasional imperfections are reminiscent of the way we make sense of memories—the familiar elements are there (friends, family, work, hobbies) but they seem to have lost their distinct contours—they lack identifying characteristics. They become a series of repeated symbols, notches along the linear path of time, but disorienting in their sameness. Umemoto’s structures are similarly uncanny in that they straddle the line between the familiar (recognizable shapes, Modernist lines) and the surreal (otherworldly mazes, Escherian loops). Many of his concrete works recall ruins, either ancient or futuristic. Some feel distinctly rooted in time, summoning the brutalist social housing of post-war East Berlin. Others use an entirely new language, like remnants of a bygone civilization discovered on another planet.

Unable to access his studio for a period of time, Umemoto began Kirigami-inspired paper folding as a way to keep his practice alive. Guided by his early experiences as an architect (working toward a clear objective under a set of explicit constraints) he used limitations (no glue, no adhesive, just cuts and folds) to his advantage, creating intricately stacked monuments. Living in a time of extended limitations, we’ve been forced to get creative with what we have. Umemoto’s Vernaculaires Extraordinaires asks us to imagine what might be possible. It extends the architectural tradition of dreaming big after a period of struggle. Just as Brasília (an experiment in modernist urbanism, built from scratch and inaugurated as Brazil’s capital in 1960) sprung up as a beacon of hope for the future, or as inexpensive and reliable concrete was innovatively used to rebuild a war-torn Berlin, we are asked to investigate where we are in the dystopia to utopia pipeline—often our built environment offers the first clues.