Diana Thorneycroft: Canadians and Americans (Best Friends Forever… It’s Complicated)

Text by Natasha Chaykowski

Vexed, irresolute and complex are perhaps some of the most apt words to describe the relationship between Canada and the United States. “Complicated” is another appropriate adjective to tell of the cultural, historical and political dynamics of these national entities, and is how Diana Thorneycroft articulates a friendship between the two. In her most recent series of photographic works, Canadians and Americans (best friends forever… it’s complicated), she has produced a suite of theatrical and at times humorous mise-en-scènes that conjure the drama and intricacy of a complicated friendship.

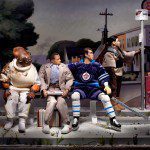

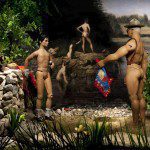

Thorneycroft’s carefully composed tableaux are staged against the canonical backdrops of well-known paintings; the quintessentially sublime cliffs of Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer Above The Sea Of Fog, J. E. H. MacDonald’s mountainous landscape, and Andrew Wyatt’s idyllic and pastoral plains from Christina’s World are some of the painterly locales that set the scenes of Thorneycroft’s photographs. These recognizable backgrounds host her imaginative ruminations on the respective cultures of Canada and our neighbour to the south.

Where figures exist in such paintings, they are replaced in Throneycroft’s works by figurines—Barbies, action figures, dolls—in the company of meticulously detailed accessories, other bits of scenery, and plastic props. The woman crawling through the tawny field, her back turned from the viewer, in Wyatt’s painting, is replaced by a doll, who remains prostrate in Christina’s World (Gets Turned Upside Down by Cpl. Dew Wright) (2012). In Thorneycroft’s version however, an RCMP officer, pointing a gun at the house in the distance, lies on top of the woman, suggesting that he is protecting her. This addition of Canadian iconography onto the surfaces of an iconic American painting speaks to the artist’s interest in the distinctions between the two cultures. She unfurls this relationship further in adding characters to otherwise figure-less paintings in other works in the series.

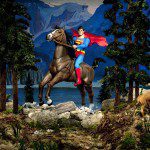

Such is the case in Lake O’Hara (Clark, Northern Dancer and the Evil Weasel) (2012), in which a Superman figure strikes a pose astride Northern Dancer, the first Canadian horse to win the Kentucky Derby. In MacDonald’s original, a clearing in the foreground allows for a vignetted view of the famous turquoise waters of British Colombia’s Lake O’Hara. Here, a classic American hero boldly occupies the otherwise pristine Canadian landscape, a comment on the infringement (or threat of infringement) of powerful American forces.

While these works feature one or two dominating cultural references, many of the images in this series are populated by a teeming number of figures and objects, creating a cacophony of cultural symbols. Sometimes the relationship between Thorneycroft’s many allusions is obvious, while at others, the profusion of references is productively harder to grasp; it requires some work. In this way, these images demand of the viewer a performance of the friendship they address, which is a friendship that is forever demanding of work, and necessarily complicated.