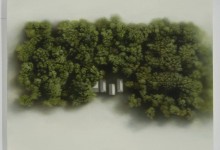

In her work, Melissa Doherty forces us to scrutinize the landscape, to survey it – or, at least, she makes us aware of our perceptions of it. The paintings that she presents in her exhibition Vignette, square or almost square in shape, show pieces of territory in which nature is largely dominant, with roads and habitable structures inserted and aligned. We see the landscapes from almost directly above, so that we lose all sense of volume of the landscape in favour of the geometry of roofs and the strange vitality of greens extending to the edge of the composition. It is as if these organized zones, isolated on a white background of oil paint and brushstrokes, form a critique of our expectations of and interventions in nature, and of how we structure our territories. It is a social topography; the aerial point of view brings to mind the highly topical question of how territories are kept under surveillance and appropriated. The famous American urban planner Kevin A. Lynch saw the organization of the landscape as having a radical effect on human behaviour – that is, the organization of the spatial information surrounding us changes our perception of spaces, our ways of living in them, and our modes of conceiving of them.

In her paintings, Doherty turns her attention to the ways in which nature is modified, if not manipulated. She is interested in the artifice of “architectured” landscapes, and she captures them in a way that resembles models or even still lifes. The view is static, the subject apprehended under the layer of colours skilfully laid onto the canvas. The view enables us to attentively observe the territory and how it is structured, but also how it has been taken over by human beings and immunized. For the artist, this alternative vision of the landscape also evokes the sensual aspect of the materials that she has found in the groves of trees, which we want to reach out and touch as we might caress a bolt of rare cloth or precious fabric.

Despite the distance imposed upon us by the point of view, and the uncompromising restructuring to which nature must submit, these landscapes nonetheless have a “tactile and comforting” side. The use of oil paints renders the lines both precise and uncertain, both determined and diverted by the canvas that has absorbed them into its mesh. It is as if we are seeing a hyper-realist painting that has been subjected to a slight photographic blurring and is presented to the viewer in a range of colours muffled by the thickness of the atmosphere, as well as by the delicate subjectivity of the gaze that lights upon and penetrates the foliage of the trees, that lights upon the surface of the painting and penetrates the folds of the artist’s portrayal.