Text by Ming Lin

In 1914, a group of intrepid young men set forth into the northern wilderness with the ambition to document the uncharted territory of the Canadian collective unconscious. Their medium was that of sketchbooks and paint, and with these they rendered a vast and previously unknowable landscape into a tangible national identity. One could call their distinct style picturesque, as it cohered to many of the attributes prescribed by 18th century thinker William Gilpen – for capturing nature so as to make it both palatable and empowering for the viewer. During the romantic period in Europe, certain visual tropes emphasized the beauty of the natural landscape despite the rapid advancements of industrialism. As such, the picturesque, when applied properly, enabled the viewer to apprehend and revel in the vastness of change and opportunity with which they were presently confronted.

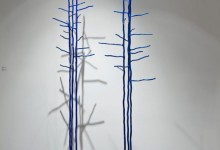

It is at a similar juncture that we contemplate the works of contemporary sculptor and installation artist Shayne Dark, who’s large scale arborescent schemes present a striking encapsulation of both the magnitude as well as the limits of our natural resources. In an age where the re-assessment of our modes of production and consumption has become a main constituent of our identity, his work serves as a potent reminder of this position’s precarity. One piece resembling a cluster of branches, for example, balances in a tenuous fashion, relying on the equal distribution of weight among all its parts to stay upright. In another work, the boughs extend upwards from a base so small it threatens to tip over. As opposed to the romantic and idealized conceptions of a nature as realized in the compositions of the Group of Seven, Dark, by working in the industrial material of hot forged steel, acknowledges the imprint of the human hand on our surroundings.

As art critic and theorist Rosalind Krauss has noted, sculpture, by nature of its hefty form, has its own internal logic: “It sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place” and, as such, becomes a “commemorative representation”.1 Dark’s sculptures’ metallic sheen lends them an allusion to permanence; they become monuments to life forms which are quickly being depleted. Dark’s enframement of these organic shapes in precious materials allows the viewer to apprehend the infinitude of natural beauty which surrounds us. It is also an opportunity to confront the scope of our impact on the environment and to take heed of the changes which inevitably ensue. The tension produced between the supple but solid metal and its ephemeral subject matter, between the natural and the unnatural, moves us beyond the realm of picturesque and into the sublime.

1. Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring, 1979): 33.