Opening reception: Saturday, September 13, 2025 from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m.

Heather Shillinglaw: Nats’edé (People are coming)

Text by Andrea Valentine-Lewis

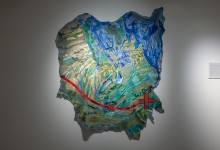

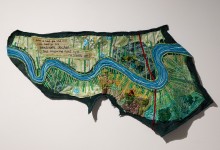

Land is like us, and we are connected conceptually to it – our bodies and minds are like neurons with electrical pulses. Flower stems and leaves connect, ghost rivers and lakes interweave with the North Saskatchewan River. The eagle eye is stitched into deer hide, blended with paint, ribbons, fabrics, hand beading, yarn tufting, and thread painting. As I assemble this, [I] encourage us to remember, remember, remember the land as it once was – remember my ancestors and how they lived within the landscape.

–Heather Shillinglaw

Shillinglaw is an Edmonton-based multimedia artist working across needlework, beading, and collage, employing both traditional and contemporary modes of making to share the oral histories from her ancestors of Scottish, French, Anishnaabe, Nêhiyawêwin Cree, and Denesųłįné heritage. Her multilayered family history initially inspired her artistic journey, as she learned about how the nohkoms–her grandmothers and great-grandmothers–were instrumental as translators for the Hudson Bay Company due to their knowledge of several Indigenous languages and the intricacies of the landscape. Women’s stories and teachings continue to be a central motivation for the artist’s practice.

Nats’edé (People are coming) presents a new body of work inspired by both the Ministik Mihkinâhk (“Turtle Island” in Cree) creation story, as well as the histories of ancestral harvesting sites and ethnobotanical knowledge of her homelands told by her mother, Elder Shirley Norris/Shillinglaw. The artist carried out additional research, consulting with ecologists and biologists about the historical and continuous environmental shifts imposed on the landscape. This research became the blueprint for building out her map-like tracings of her ancestral histories.

Each composition recites an important familial story around four central and sometimes overlapping themes: residential schools and Shillinglaw’s drive to reclaim lost languages in her works’ titles; family, specifically the women and their knowledge of trails for trade; her mother and grandmother; and the ecology of Turtle Island, including ecological loss due to ongoing resource extraction and climate change.

For Shillinglaw, each coloured thread, ribbon, and stitched poem reveals an important aspect of a land-based story: white threads throughout the blue threads of the water signal ecological loss or “ghosts in the land”; red ribbons mark trails, also known as the “pockets in our skin”; and orange ribbons and red Xs mark the location of residential schools and unmarked gravesites.

Shillinglaw’s works exist in a space rich with possibility–between loss and reclamation, between tragedy and hope, and between stories past and storied futures.

My elders say that knowledge and stories are developed to preserve culture, and art is the key. [It is a] way for us to move past intergenerational trauma and is a tribute to our ancestors, as history that is not forgotten lies within their troubled lives.

–Heather Shillinglaw