Diana Thorneycroft: A People’s History

Post-colonialism has taught us that history is multifaceted, and can never be a straightforward narrative from a single point-of-view. When considering stories of the past, we collectively need to ask: Whose history is being remembered; whose recollections are recorded and on what terms? Who will talk about what the disenfranchised will have to endure if they are voiceless?

Thorneycroft voices the stories of the marginalized in her series A People’s History, a group of images that clearly evolved from her works Group of Seven Awkward Moments and the Canadiana Martyrdom Series, with their kitschy Canadian icons and archetypical wooded landscapes as backgrounds. She crafts and captures events in Canadian history that people are disinclined to claim as their own. These scenes are enacted using tinker toys, which come across as both didactic tools and horrifying misappropriations. Thorneycroft points out that these images all involve the disadvantaged, the uneducated and the young – populations that are frequently overlooked and whose grievances go unheard.

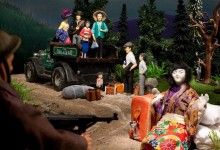

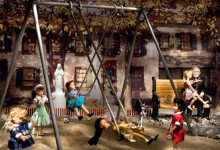

One particularly striking and complex photograph is Quintland, a depiction of the lives of the Dionne quintuplets who were born into a media frenzy, and their existences were turned to profit. We find a landscape painted in the background, very much in the realm of the Group of Seven, depicting the harsh and rugged landscape often associated with Canada. Snow-capped plastic trees complete the effect of a strange and unnatural version of nature. The viewer is situated in the foreground of the image within an outdoor playpen, protected by wood fencing and barbed wire. The girls roam happily around the pen in candy-coloured garb: one rides a bike, another climbs the jungle gym and their playthings are scattered around the contained lawn. Up close, it becomes apparent that the girls wear handcuffs, and these shackles provide the viewer with a clear message about their oppression, and add another layer of physical containment. The little dolls used to build the scene could have easily been sold at the Quintland gift store years ago. On the right, a doctor stands, equipped not only with his medical equipment but also a camera, prepared to snap photos for public consumption. He is not alone is his voyeurism: a busload of tourists take pictures from the safe vantage of their tour bus and nearby a family has made a vacation of coming to observe them, to inspect the spectacle. Thorneycroft reminds us with A People’s History that history can only be encapsulated reluctantly, with a kind of arbitrary closure, and that we should beware of the empty promise of happy endings.