Eric Lamontagne : Road Paintings

On the Road

Text by James D. Campbell

“THE only ones for me are the mad ones,” commences Jack Kerouac’s legendary sentence. “The ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars . . .”

Well, Eric Lamontagne’s recent paintings effortlessly – and one might even suggest furiously – invoke the “old going road” of the Beats as they raced across the American landscape with devil-may-care frenzy and abandon. Kerouac composed the first version of one of the most famous books of the 20th-century in three weeks, in 1951, on a continuous scroll of drawing paper so he would never have to stop at a creative red light. Similarly, Lamontagne’s paintings are kinetically charged and entirely relentless in their morphological mien. He uses digital photographic means to overhaul the conventions of painting, imbuing it with new meaning, and making it at the same time new and strange and compelling.

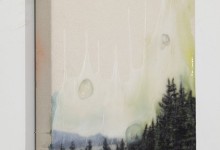

In these recent abstract landscape paintings, Lamontagne summons up a sense of progressive mutation and flux which owes less to the fragmented photographic palimpsests on which they are based than on our own sense of the landscape at risk, changing and devolving at an accelerated pace, just as the tenses we now inhabit seem more future than present or just-past. Thus, there is not one iota of déjà vu in his paintings, the methodology of which is cutting-edge and more about Supermodernity (as French theorist Marc Augé meant it in books like his seminal Non-lieux) nipping at our heels than hearkening back to the prose of yesteryear. Still, it is hard not to think of Lamontagne as a kindred spirit of Kerouac. The poetics of his work is equally diverting, enlivening, and never, not once, not ever, static or predictable. He deconstructs and folds space as rigorously and well as he displaces the viewer he carries into that space, making the assimilation of his work a heady and instructive experience, indeed.

Lamontagne’s roadtrip is hallucinatory in intention, palette, and the perceptual pirouettes he performs and insists his viewers perform alongside him. His works explode like spiders across the stars and his viewers’ optic array. This is a surreal order of interactivity required by few of his peers. And Lamontagne is a painter who has consistently refused to rest on his laurels. He is always on the move, on the road, redefining space and time as only the most gifted artists can. In this sense, he reminds us of the hyper-charged and driven persona of Dean Moriarty (based on Neal Cassady) who invests On the Road with such a Paul Virilio-like and vertiginous rush of speed, images and anamorphoses.